What Sinners and Social Media Can Teach Us About Discourse in 2025

- Caleb Lee

- Nov 29, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Nov 29, 2025

Sinners (2025), widely regarded as one of the year’s best movies, has everything going for it heading into the upcoming awards season. It entertained audiences, made a lot of money, effortlessly blended genres together, and offered a critique of African-American oppression—all qualities that have contributed to its unprecedented popularity as a miniature cultural moment. As a box-office hit, far more people have seen it than they have most of its competitors: For instance, at the time of writing, Paul Thomas Anderson’s One Battle After Another is projected to lose $100 million worldwide despite enjoying similar critical acclaim. Sinners, meanwhile, collected over $366 million globally, making it the highest-grossing original film of the last 15 years. This level of recognition in our social media-dominated world means there are more TikToks, Reels, forums, and YouTube videos discussing the movie and circulating the web than most films will ever generate. But this much attention around a culturally important, original blockbuster might not be such a good thing, as the toxic discourse surrounding Sinners has exposed how our online behavior is devolving into a new, identity-based way of perceiving entertainment.

Although this article isn’t really focused on Sinners as a movie, I’d like to disclose that I wasn’t the biggest fan of it. I thought that the writing was shoddy, that it relied on some heavy horror clichés and poor decision-making from the characters, that there were notable inconsistencies (vampires alternating between burning instantly in daylight and being able to resist, depending on which was convenient for the moment), and that the final 20 minutes were so out-of-left-field that a number of people in my theater got up and walked out. I was shocked to find out afterward that so many people loved the movie. So naturally, I spent the next two hours sitting in the parking lot, scrolling through threads and “ending explained” videos in hopes of finding what I might have missed.

I didn’t find anything, but it was pretty clear from the start that there wasn’t your “normal” online discourse for this movie, at least not on any of the sites I visited. Under a generally reasonable Reddit post titled “Why Sinners (2025) isn’t a great movie and how fake positive reviews are killing cinema” (which weirdly doesn’t tackle fake positive reviews at all), one of the top-rated replies at the time read, “Looks like it’s hard for you to grasp because these things may not all come together to affect your life and history significantly and you can’t step outside of yourself to see the value for those who actually have to fight these demons and still do today… You don’t get it because you don’t have to, nor do you seem to want to, and I’m not surprised.” This was in response to a person saying the different plots didn’t fit together to form a convincing structure, and there were some “loose ends” that the movie needed to tie up.

A different tweet and its subsequent replies saw Sinners detractors labeled as uneducated, racist, or, in one case, “sounding like a Klan member.” Someone on Reddit said, “This movie is simple to understand if you can remove yourself from the basic mindset… Sinners is deeper than the average, privileged, unthreatened person could ever grasp.” Another assertion, this time presumably from a Black commenter, read, “You don’t like the movie, that’s OK. It wasn’t meant for you. It wasn’t made for you, it was made for us by us. You can go. You can even enjoy it if you want to, but the layers and the hidden meaning behind this film were not intended for people like you.”

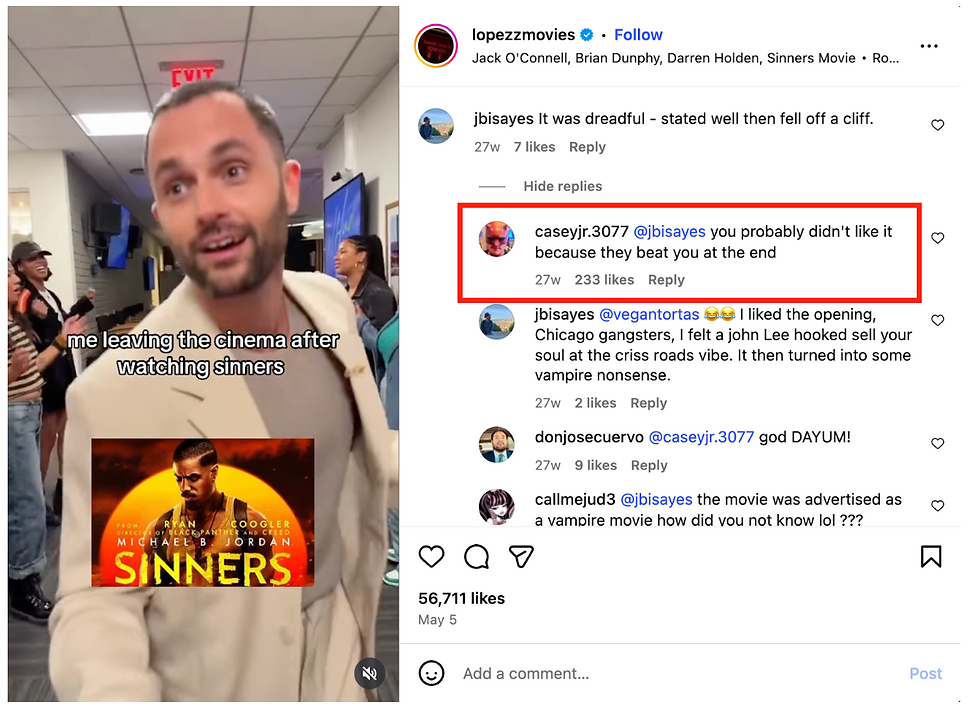

Now, I’m sure there have been hundreds upon hundreds of racist remarks about this movie—I saw some utterly despicable ones myself—which are sadly indicative of the time we live in now. But the comments cited above all came in answer to people who, like me, were genuinely confused about how Sinners’ many motifs came together to form a coherent message. At first, I thought the abrupt, violent backlash to some negative reviews might be because the film had reached theaters and people were eager to defend it, but after keeping an eye on social media conversations in the six months since, it seems like accusatory rhetoric is more prevalent than ever. (A quick search for “Sinners” posts on Instagram will tell you everything you need to know.)

So why are people getting called colonizers for disliking a movie now? Well, as mentioned before, Sinners has established itself comfortably among the all-time box office earners, standing as North America’s second-highest-grossing horror movie ever and one of the highest-grossing original films of this century. That means it’s very likely that people who aren’t so passionate about film make up a large portion of Sinners watchers, but maybe haven’t seen this year’s other critically acclaimed films like One Battle or After the Hunt. Naturally, it then makes sense that the online discourse about this movie is more volatile. If I had previously only watched Superman and A Minecraft Movie in 2025, I too would be bursting at the seams to talk about something as racially charged and relevant as Sinners. In this way, because the movie reached an audience far beyond the typical cinephile or arthouse crowd, much of the public discussion was about Sinners as a cultural statement of identity and struggle. Because of that, disliking the movie on the merits of its structural choices could be seen as rejecting everything it represents.

A somewhat connected possibility has to do with the rise of online virtue signaling in general. As social media has become more prevalent over the years, and because of the current politically charged state of our country, virtue signaling on online platforms has become more common; in fact, a study this year found a growing correlation between such virtue signaling and social narcissism. For audiences of an African-American directed blockbuster about taking over one’s identity and the cycle of systemic inequality that makes the oppressed the oppressor, other films might have inspired the same sense of awe and passion—but Sinners seems like the obvious choice to express their views online. This reaction, however, isn’t only about morality: it provides real-time insight into our growing lack of communication skills, especially as they relate to media, caused by our beloved, destructive “social” Internet platforms.

In an environment where algorithms prioritize outrage and certainty over nuance, now more than ever, pushing “angry” content onto users’ feeds to increase engagement, people are more angry, yes—but we’re also being trained to deliver our statements in the most emphatic, simplified ways possible to perform our ideal identity. As platforms like X and TikTok reward opinions that are the loudest and most confident, we are slowly drowning out voices that don’t belong to—in the case of Sinners—the categories of “you get it and are morally correct” or “you don’t get it and are evil.” That is to say, because of social media’s click-greedy design, we are experiencing a collective failure to think outside the black and white, instead settling for the binary categories that platforms have designed to rile us up: like and dislike, correct and incorrect, moral and immoral. The way we interact with others online isn’t anything like how we talk to each other in person, but the Internet’s exploitation of our feelings is what keeps people pursuing this hostile, sweeping cycle of virtue signaling. When an Instagram commenter angrily insists that you just don’t understand Sinners, maybe it’s less about the movie and more about conforming to a simple, easily accessible identity. “Understanding” is cinema-related social media’s way of belonging.

Is it really plausible that this aggressive discourse about a single film could stem from our screen-amplified desire for acceptance and the ever-expanding deafness of Internet interaction? All I can say is that I’m pretty critical of Sinners—but in over 45 in-person conversations with Columbia students about this movie, I haven’t been called a Klan member even once.

Caleb Lee is a first-year writer for Double Exposure. He is best known for his work on “What Sinners and Social Media Can Teach Us About Discourse in 2025.” The only movie he has ever cried at is The Tree of Life.